When the Bow Vestry initially asked Passmore Edwards to support the funding of a Free Library their request was not favorably received. However, he eventually agreed to provide £4000 towards the building.

The Parishes of Bromley and Bow initially proposed combining to provide a central library and a branch library in each Parish but as soon as an agreement appeared to have been reached, negotiations broke down. Bromley had already opened a branch library at Brunswick Road in 1895, Passmore Edwards performing the ceremony but not contributing to the costs other than by giving his customary 1,000 books, and it was mainly due to the inability of the Bow Vestrymen to agree amongst themselves that lead to the breakdown and the decision to go it alone. In November 1898 the Clerk to the Bow Vestry, wrote to Edwards to ask for his assistance. His response what that he was unable to help at that time but a second request resulted in an offer of £4,000.

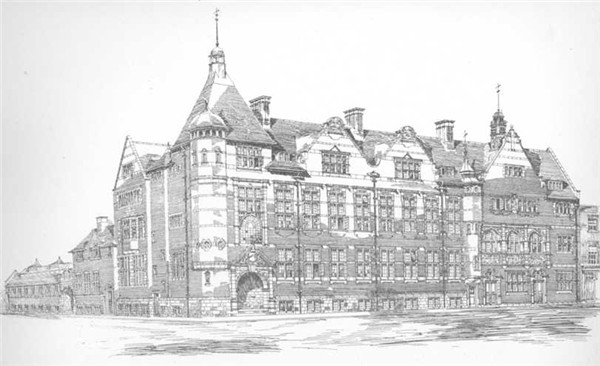

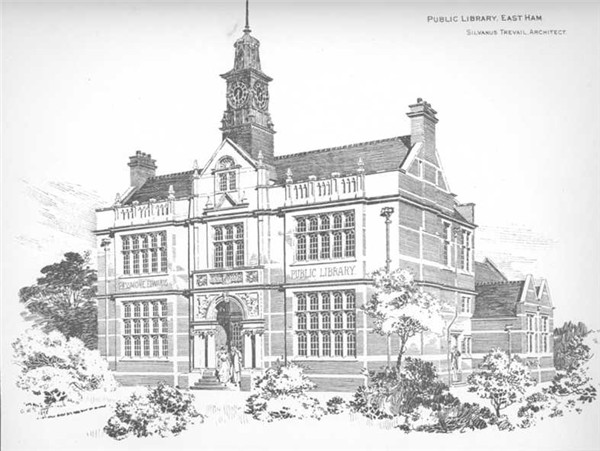

Designed by S B Russell, who also designed the Plaistow Library and the West Ham Museum, the Bow library was constructed on a salt glazed brick base with redbrick elevations and Portland Stone dressings. There were the usual arrangements for reading room, reference and lending library, with shelving for 12,000 books, but a feature of the library was the heating arrangements, with hot water piped under the road from the public baths and wash house opposite.

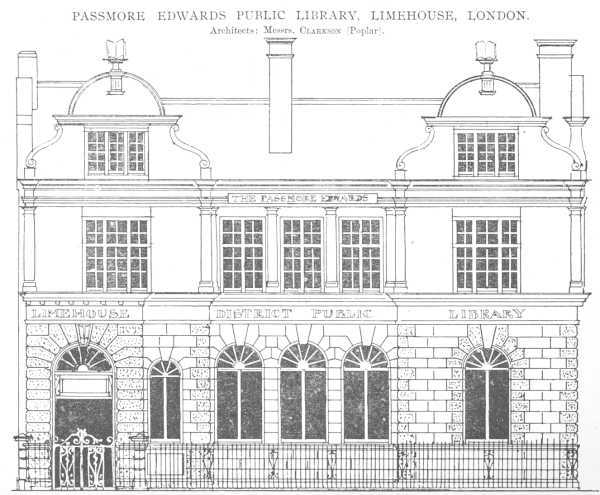

The date set for laying the foundation stone was Friday 19 October 1900, at 4 o’clock, after laying the foundation stone at Limehouse at 2.30. The previous day Edwards had reopened the West Ham Polytechnic, which he had not funded, and attended the opening of the adjacent West Ham Museum, which he had funded, and had witnessed the unveiling of a bronze bust of him at the Museum. Not only were the foundation stones for the Limehouse and Bow libraries laid on the same day, they also opened on the same day, 6 November 1901.Plans to extend the Bow library were proposed in 1926 but it was not until 1939 that work commenced, only to cease when the war started and instead a public air raid shelter was built on the site. Bomb damage occurred in 1940 but the library was only closed for a few weeks, and building recommenced in 1949, the extension finally opening in February 1950.

However, 1962 marked the end of the library service at the Roman Road premises, when a new library and community centre was opened in Stafford Road, nearby, and the Passmore Edwards building was converted into a public hall, called Vernon Hall. This library was itself replaced with the formation of the present library, the Idea Store, in 2002, situated just behind the original Passmore Edwards building.